A Single Battery Fire Brought Down an Entire Government

How South Korea's Data Center Disaster Exposed the Dangers of Centralization

Executive Summary

On September 26, 2025, a lithium-ion battery fire at South Korea's National Information Resources Service (NIRS) data center in Daejeon triggered what security experts are calling a 'digital Pearl Harbor' for the nation. A single exploding battery during routine maintenance brought down 647 government systems simultaneously, paralyzing essential services for millions of citizens and exposing catastrophic failures in disaster recovery planning.

Two weeks after the incident, only 157 services have been restored—a recovery rate of just 24%. Even more shocking: 858 terabytes of government data stored on the G-Drive system—representing eight years of work for 125,000 civil servants—has been permanently lost. Officials admitted there were no backups, claiming the system was 'too large' to back up.

The human toll has been devastating. Four people have been arrested for potential negligence, and a senior government official overseeing restoration efforts died by suicide, jumping from a building. The incident serves as a stark warning about the dangers of over-centralization and the critical importance of proper disaster recovery infrastructure.

The Incident: How It All Went Wrong

A Routine Maintenance Task Becomes a National Crisis

At 8:20 PM on Friday, September 26, 2025, technicians at the NIRS data center began what should have been a straightforward task: relocating uninterruptible power supply (UPS) batteries from the fifth floor to the basement. The batteries, manufactured by LG Energy Solution and installed in August 2014, were being moved precisely because of fire safety concerns—they were positioned just 60 centimeters from major servers.

During the disconnection process, one battery cell failed catastrophically. The failure triggered a thermal runaway event—a chain reaction where overheating in one cell causes adjacent cells to overheat and fail. Within moments, temperatures soared past 160°C (320°F), and all 384 lithium-ion battery modules erupted into an inferno that would burn for 22 hours.

The batteries had been in service for more than 11 years, exceeding their 10-year recommended lifespan by over a year. While they had passed safety inspections as recently as June 2025, the aging cells proved catastrophically vulnerable during the relocation procedure. Industry experts suggest that technicians may have disconnected wiring before fully shutting off power, potentially triggering a voltage spike that caused the initial cell failure.

The Fire That Couldn't Be Stopped

Firefighters arrived quickly, deploying 101 personnel and 31 fire vehicles. But they faced an impossible challenge: water-based suppression systems couldn't be used because flooding the data center would destroy the very systems they were trying to protect. Instead, they had to rely on carbon dioxide fire suppression, which proved painfully slow against the intense heat of burning lithium-ion batteries.

The fire wasn't declared fully extinguished until 6:30 PM on Saturday—nearly 22 hours after it began. By that time, the damage was done. The fire destroyed critical cooling and dehumidification systems, forcing operators to shut down all 647 government systems housed at the Daejeon facility to prevent heat damage to servers.

The Catastrophic Design Failures

All Eggs in One Basket: The Centralization Disaster

The NIRS operates three data centers across South Korea—in Daejeon, Gwangju, and Daegu—housing approximately 1,600 government systems in total. On paper, this appears to provide geographic redundancy. In reality, the distribution was dangerously lopsided: more than 40% of all systems (647 out of 1,600) were concentrated at the single Daejeon facility.

When fire struck Daejeon, all 647 systems went offline simultaneously. This included:

- Government24, the primary portal for citizen services

- Korea Post online banking and delivery tracking

- The 119 emergency call location tracking system

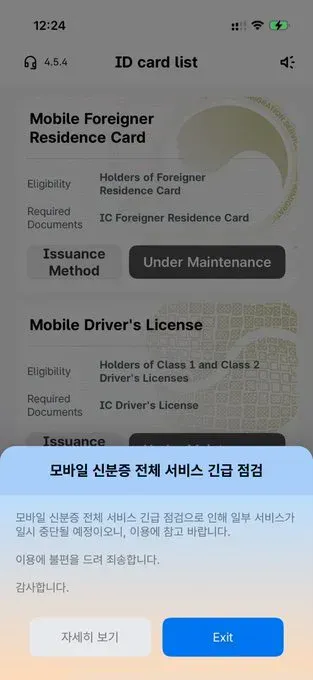

- Mobile digital ID verification (still non-functional weeks later)

- Citizen authentication and identity systems

- Tax filing and payment systems

- Government email and internal communications

- Airport security and mobile ID verification

Transportation discount verification and postal banking

Services at the other two locations continued to function, but they couldn't pick up the slack. The systems weren't designed for failover—there was no 'twin server' architecture that would allow backup sites to automatically take over when the primary location failed.

No Failover, No Redundancy, No Real-Time Backup

The absence of active-active redundancy proved to be the government's fatal flaw. In modern cloud architecture, critical systems typically employ real-time failover capabilities—if one data center goes down, traffic automatically redirects to backup servers that are continuously synchronized with live data. The NIRS lacked this basic protection.

Vice Interior Minister Kim Min-jae admitted that the facility had no 'twin server' architecture. Even though backup facilities existed in Gwangju and Daegu, services couldn't switch over in real time during the outage. The systems simply went dark, leaving citizens unable to access essential government services for days or weeks.

"The government should have learned from the 2023 incident and implemented active-active redundancy, where backup servers synchronize in real time."

—Information Security Expert

This wasn't even South Korea's first rodeo. In November 2023, a similar network outage disrupted government services, prompting criticism about the lack of data redundancy. A disaster recovery center in Gongju had been completed in May 2023 but remained dormant due to budget constraints—25.1 billion won ($17.9 million) allocated for IT infrastructure in 2024 went unspent. The warning signs were there; they were simply ignored.

The G-Drive Catastrophe: 858TB Lost Forever

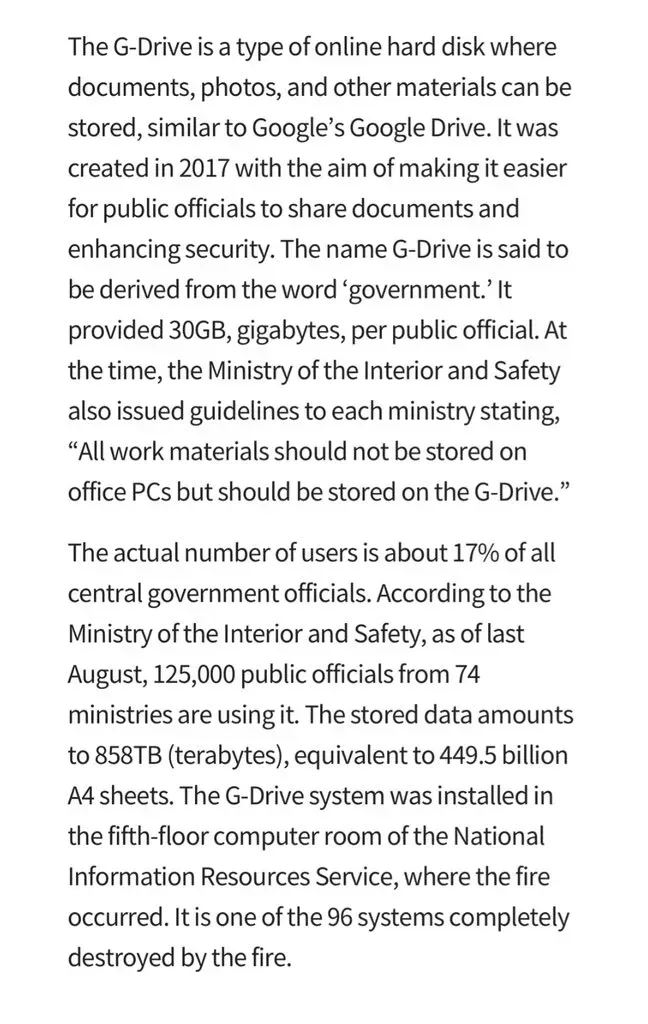

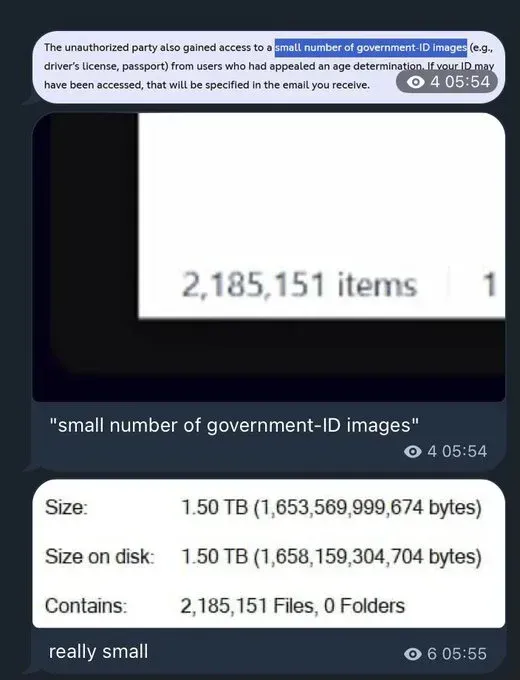

Perhaps the most shocking failure involved the G-Drive system—the government's internal cloud storage created in 2017 specifically to ensure data sovereignty and maximize security. The name 'G-Drive' stands for 'Government Drive' (not to be confused with Google Drive). About 125,000 civil servants from 74 ministries—approximately 17% of South Korea's 750,000 government employees—used the system. Each employee was allocated 30GB of space to store work documents, reports, and files.

When the fire destroyed the G-Drive servers located on the fifth floor of the NIRS building, 858 terabytes of data vanished—equivalent to 449.5 billion A4 sheets. The truly staggering part? There were no backups. Not external hard drives. Not cloud backups. Not off-site storage. Nothing.

Officials offered a jaw-dropping explanation: "The G-Drive couldn't have a backup system due to its large capacity." This reasoning defies basic disaster recovery principles. The 3-2-1 backup rule—three copies of data, on two different media, with one copy off-site—exists precisely for large-scale systems like this.

The government had actually mandated that employees store all work files exclusively on G-Drive rather than on local PCs—a security measure designed to prevent data leaks and ensure data sovereignty. Ministry of Interior and Safety guidelines explicitly stated: 'All work materials should not be stored on office PCs but should be stored on the G-Drive.' This policy, intended to enhance security, instead created a catastrophic single point of failure.

The Ministry of Personnel Management was hit hardest, as all affiliated officials were required to use G-Drive. One official lamented: 'It's daunting as eight years' worth of work materials have completely disappeared.' Another source from the ministry stated: 'Employees stored all work materials on the G-Drive and used them as needed, but operations are now practically at a standstill.' While some data may be recoverable from the Onnara system (which stores official documents submitted through formal procedures), the vast majority of working files, drafts, research, and daily operational materials are gone forever.

The Human Cost: Tragedy and Accountability

A Death Under Pressure

The disaster claimed a life beyond the initial fire. A 56-year-old senior officer in the Digital Government Innovation Office, who had been overseeing efforts to restore the data center, died by suicide on Friday, October 4—jumping from a building in Sejong City.

The man was found in cardiac arrest near the central building at the government complex at 10:50 AM. He was rushed to a hospital but died shortly afterward. His mobile phone was discovered in a smoking area on the 15th floor of the government building. He had been directly involved in managing the data center network restoration following the fire.

While Korea's Ministry of Interior and Safety stated he was not involved in the police investigation into the fire itself, the circumstances surrounding his death—including whether overwork was a contributing factor—are being investigated. The tragedy underscores the immense pressure government officials face when critical infrastructure fails and the human toll of such disasters extends far beyond technical recovery metrics.

Criminal Investigation: Four Arrested

Police have arrested four people as they investigate whether professional negligence contributed to the fire. The arrests suggest this may have been more than just an unfortunate accident—there may have been procedural failures, inadequate safety protocols, or negligent handling of the battery relocation that turned a maintenance task into a national catastrophe. A 20-member task force is conducting the investigation, including three lithium battery experts who are assessing whether outdated components, mishandling during relocation, or inadequate oversight by contractors managing the server room contributed to the incident.

The Impact: A Nation Brought to Its Knees

Essential Services Paralyzed

The immediate impact was devastating. Citizens couldn't access basic government services. The 119 emergency system—South Korea's equivalent to 911—lost its geolocation capabilities, making it harder to dispatch ambulances and fire trucks. Airport security struggled without mobile ID verification. Postal workers couldn't process packages. Tax deadlines had to be extended because citizens couldn't file returns.

Two weeks after the fire, citizens still cannot log into the mobile digital ID app—a critical service for identity verification across government and private sector services. The app displays an 'Under Maintenance' message, with notifications apologizing that the service is temporarily suspended due to an emergency server issue.

Of the 647 systems that went offline, the government designated 36 as 'Grade 1' services—those deemed absolutely essential based on user impact and service importance. Even two weeks after the fire, only 21 of these critical systems (58%) have been restored. The recovery timeline keeps getting extended. Initially projected at two weeks, officials now estimate it will take four weeks or longer to fully recover the 96 systems that were directly destroyed.

Economic and Social Costs

The economic toll extends far beyond the immediate firefighting and recovery costs. Every hour of downtime represents millions in lost productivity and economic activity. Small businesses that rely on government verification systems for transactions face revenue losses. Citizens waste time trying alternative channels for services that should be instantaneous online.

The incident happened just before Chuseok, South Korea's major holiday period in early October, amplifying the disruption as millions of people traveled and needed government services. President Lee Jae-myung apologized publicly: 'The public is experiencing great inconvenience and anxiety because of the fire. As the nation's top executive, I offer my sincere apologies.' But apologies don't restore lost data or fix systemic infrastructure failures.

Damaged Reputation

For a nation that prides itself as a global technology leader—South Korea ranks fourth in the 2025 Global Innovation Index—this disaster is humiliating. The Hankyoreh newspaper called it 'a flabbergasting disaster in a country that calls itself an IT powerhouse.' International observers are questioning how a technologically advanced nation could make such fundamental mistakes in data center management.

The Lessons: What Every Organization Must Learn

1. Geographic Distribution Is Not Real Redundancy

Having data centers in multiple locations means nothing if they can't actually fail over to each other. True redundancy requires active-active architecture where backup systems are continuously synchronized and can instantly take over if the primary location fails. Simply spreading servers across different cities provides no protection if each location operates independently.

2. There Is No Excuse for Not Having Backups

The claim that the G-Drive 'couldn't have a backup system due to its large capacity' is indefensible. Organizations routinely back up petabytes of data using tiered backup strategies—frequent backups of recent changes, less frequent backups of older data, and long-term archival storage. At 858TB, G-Drive wasn't even particularly large by modern data center standards. Modern cloud infrastructure makes backing up such systems standard practice.

The 3-2-1 backup rule exists for a reason: three copies of your data, on two different types of storage media, with one copy stored off-site. This isn't optional for critical systems—it's the bare minimum. The cost of implementing proper backups pales in comparison to the cost of permanent data loss and the devastation of losing eight years of work for 125,000 employees.

3. Mandatory Centralization Creates Mandatory Failure Points

Requiring all employees to store files exclusively on G-Drive, while banning local storage for security and data sovereignty reasons, created an all-or-nothing scenario. Security policies must be balanced against resilience. A better approach would have been mandatory synchronization of local files to cloud storage, providing both security and redundancy—or at minimum, implementing proper off-site backups of the centralized system.

4. Lithium-Ion Batteries Are High-Risk Components

This is not South Korea's first lithium battery data center fire. In October 2022, a similar incident at an SK C&C data center in Pangyo disrupted the KakaoTalk messaging platform, affecting millions of users. The pattern is clear: lithium-ion UPS systems, while space-efficient and cost-effective, pose significant fire risks that require:

- Aggressive replacement schedules before batteries exceed their lifespan

- Physical separation from critical server infrastructure

- Real-time battery monitoring systems for early warning signs

- Specialized fire suppression systems designed for battery fires

Proper maintenance procedures that prioritize safety over convenience

5. Disaster Recovery Must Be Tested, Not Theoretical

Having a disaster recovery plan on paper is worthless if it's never tested. Regular drills and failover tests would have revealed the absence of real-time redundancy long before an actual disaster struck. Organizations must validate that their DR plans work under realistic conditions, with trained staff who can execute them under pressure.

Looking Forward: Can It Be Fixed?

In response to the crisis, South Korea's government has pledged major reforms. Officials vow to 'overhaul the entire security architecture from the ground up' with long-term, fundamental solutions rather than temporary fixes. The government plans to:

- Relocate damaged systems to cloud infrastructure in Daegu

- Finally activate the dormant disaster recovery center in Gongju

- Implement active-active redundancy for all Grade 1 systems

- Develop real-time failover capabilities across geographic locations

Consider leveraging private cloud infrastructure for added resilience

Whether these reforms will be implemented, or if they'll suffer the same fate as the unused 2024 IT infrastructure budget, remains to be seen. The test will come not in promises made during crisis, but in sustained investment and attention once the immediate emergency fades from headlines.

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call for the World

The South Korean data center fire is more than a cautionary tale—it's a stark demonstration of how modern dependencies on digital infrastructure create catastrophic vulnerabilities when basic precautions are ignored. A single battery failure cascaded into a national crisis because the government made fundamental errors that any IT professional should recognize:

- Over-concentrating critical systems in one physical location

- Failing to implement real-time failover capabilities

- Creating mandatory single points of failure through security policies

- Neglecting basic backup principles for massive data systems

Ignoring the fire risks of aging lithium-ion batteries in critical infrastructure

What makes this disaster particularly instructive is that it was entirely preventable. The technology for proper disaster recovery exists. The best practices are well-documented. The warning signs from previous incidents were clear. Yet the government failed to act until disaster struck—and when it did, the consequences were catastrophic: 858TB of irretrievable data, weeks of service outages, four arrests, and a death.

The human cost of this failure cannot be measured solely in technical metrics. A senior official felt such pressure and responsibility that he took his own life. One hundred twenty-five thousand civil servants lost eight years of work. Millions of citizens were cut off from essential services. The reputational damage to South Korea as a technology leader is immense.

As organizations worldwide increasingly consolidate infrastructure for efficiency and adopt lithium-ion UPS systems for space savings, the South Korean experience serves as a critical warning: the cost of cutting corners on disaster recovery far exceeds whatever operational efficiencies were gained through centralization.

For IT leaders everywhere, the message is clear: audit your disaster recovery architecture today. Map out single points of failure. Test your failover procedures. Verify your backups actually work. Because when disaster strikes, you'll measure recovery not in the theoretical capabilities of your systems, but in the harsh reality of how many hours, days, or weeks your critical services remain offline—and whether your data can ever be recovered at all.

South Korea is learning this lesson the hard way, at tremendous cost. The question is: will the rest of the world learn it vicariously, or will we wait for our own disasters to drive the point home?